Indianapolis Shakespeare Company, sporting a new name and fine prospects, puts "As You Like It" on at White River State Park

"If music be the food of love, play on," begins a famous comedy of Shakespeare's, not the one the Indianapolis Shakespeare Company (IndyShakes) is presenting this weekend at White River State Park. "Twelfth Night" has the subtitle "What You Will," a hint that the playwright is toying with the same mood of caprice and multivalence more conspicuously signaled by "As You Like It," the company's 2017 production.

The first full performance of the show came Friday night, Thursday's having been cut short by a cloudburst near the end of the first act; the run concludes tonight. Nature's capriciousness held off for the actual opening night under sunny skies. Orsino's line about music and love — and the vehicle of food that transports us into a world of ungovernable appetites — came to mind as the primacy of love in "As You Like It" was both enhanced and challenged by music.

Indeed, this production comes close to being music-crammed, to adapt an image the heroine Rosalind uses at the approach of the courtier Le Beau, "with his mouth full of news," she rightly guesses. She's the daughter of the duchy's rightful ruler, in exile in the Forest of Arden, and the inseparable friend of the usurping Duke Frederick's daughter, Celia. Perhaps the production's stepped-up focus on music makes the show more marketable, to borrow Celia's observation on the benefit of being news-crammed.

Ramon Hutchins' full-throated performances of the show's songs, accompanied compatibly by a rootsy onstage band, open and close the show. As Lord Amiens, Hutchins initially pumps up the crowd and launches the intermittent songfest, only to be cruelly checked by black-shirted ruffians in service to the usurping Duke Frederick, in Ben Tebbe's performance a vicious control freak obsessed with loyalty (why does that description feel so familiar?).

The opposition between the corrupt court and the Forest of Arden, the arena of escape where most of the action takes place, is thus brilliantly set forth in an imaginative stroke of theater. Overlaying song so thoroughly on the last scene, however, deprives the play's conclusion of an old-fashioned ceremoniousness. Shakespeare's carefully engineered happy ending becomes mainly an occasion to party. Probably Ryan Artzberger, a well-regarded actor and IndyShakes member making his debut as a director, found the symbolic figure of Hymen, who helps tie up various knots at the end, too dated.

That feeling also may have prompted the cutting of the Epilogue, which gives Rosalind her last display of humanity and gentle learning, imparting lessons in love that she has mastered over the course of the play. Understanding that almost all Shakespeare, with the possible exception of "Macbeth," undergoes trimming in modern productions, I still found some of the cuts regrettable. For instance, and at the risk of sounding all English-majory, there is a plethora of elaborate, balanced sentences and laboriously extruded conceits that characterize the language of "As You Like It." The style is prevalent in the prose romance from which Shakespeare drew his story, Thomas Lodge's "Rosalynde," which in turn reflected the gaudy "Euphues" by John Lyly, whose excess of highly ornamented prose enjoyed a vogue among word-drunk Elizabethans.

Rosalind, the heroine, the clown Touchstone, and the studious melancholic Jaques all indulge in euphuistic fancies, some of

which are lopped here. Fortunately, traces of the style remain in this production: I loved how Jaddy Ciucci's Touchstone ends a sinuous colloquy with Rosalind and Celia about honor and swearing oaths with a simulated mic drop. (Another modern touch that worked well was to have the wrestling match between the Duke's favorite, Charles, and the fraternally abused Orlando carried out in a mock video-game format.)

Speaking of Orlando, there's no reason to put off further discussion of this production's success in giving so much vitality to the love-crammed story at its center. Grant Niezgodski gave a well-balanced interpretation of the hero, destined from an early meeting with Rosalind (placed around that wrestling bout) to be the love of her life. He projected the energy and good-heartedness the role requires. Though in his Arden exile Orlando is quite manipulated by Rosalind's romantic designs (surely he must sense she's not the young swain she pretends to be), Niezgodski never seemed like her unwitting plaything.

That's vital in order to make an Orlando worthy of such an intelligent woman's love. It's hard to resist finding Rosalind so huge a Shakespearean triumph that no one else in "As You Like It" seems to matter. After all, there are other love affairs that need to come out well, and there's the political context that sets the whole court-and-country contrast essential to this play. Phebe (Claire Wilcher) must be arm-twisted to accept the romantic intensity of Sylvius (Michael Hosp, doubling wonderfully as the faithful servant Adam), the acerbic Touchstone has to find suitable an alliance with the country wench Audrey (Joanna Bennett), and the repentant, once-cruel brother Oliver (Peter Scharbrough) must see the excellence in all respects of Celia (Sarah Hunter, who solidly conveyed Celia's devotion to Rosalind).

But "As You Like It" is Rosalind's play; she dominates its small but still diffuse scale the way John Falstaff dominates the kingdom-defining "Henry IV" plays. Among Shakespeare's women, only Cleopatra has comparably colossal stature. Who can help being won over by her? She's likable from the beginning, and remains so, despite an episode of meanness when she tries to redirect Phebe's affections.

This production has a strong, winning portrayal of Rosalind by Lauren Briggeman. Her vocal command ranges from tremulous enthrallment as she falls instantly in love with Orlando, through vigorous upbraiding of Duke Frederick as he exiles her, to the credible low timbre she projects in her Arden disguise as a man. Rosalind is learning about love even as she exercises mastery over its intricacies, and Briggeman charmingly sustained that difficult balance.

That's why I would like to have heard her whole speech that ends with the marvelous rhetorical flourish: "Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love." The two examples Rosalind gives before this conclusion illustrate her good education as well as providing support for her argument. Despite their absence here, the line stunningly turns the certainty of death into something that happens "from time to time," and the decay associated with it into a peculiar phenomenon separate from and inferior to love. Rosalind lives by this paradox, by love's supremacy and its right to triumph over all odds. Seeing Rosalind in bridal dress in the last scene brings me close to tears every time, whether attending a performance or reading the play. She has learned so much, and she has taught everybody.

Two other performances stand out for me in this production: Bill Simmons, in broad-brimmed hat and loose summertime clothing as the banished Duke Senior, glides about the stage, spreading his arms as he extols the virtues of life in the forest. His sententious praise is lofted in life-affirming, motivational-speaker tones. The portrayal was just fatuous enough to be delightful without caricature. He reminded me of a typical interview guest on Krista Tippett's "On Being."

I must also mention Josh Coomer's spot-on rendering of Jaques, a lord attending Duke Senior who takes his cue from exile to become a figure of well-rehearsed melancholy, finding every human condition lamentable. Jaques' melancholy is a pose, embedded in a man feeling rootless in rusticity and casting about for a way to distinguish himself in inhospitable surroundings. To represent someone stuffed with attitudes without overacting is no small achievement, and Coomer handled it with aplomb. The touch of satire in his noble set-piece, the "seven ages of man" speech, helped it be the kind of highlight it's supposed to be.

[Photos by Julie Curry]

|

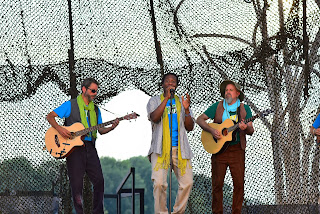

| And the band played on: The songs were peppy, but challenged the action. |

Indeed, this production comes close to being music-crammed, to adapt an image the heroine Rosalind uses at the approach of the courtier Le Beau, "with his mouth full of news," she rightly guesses. She's the daughter of the duchy's rightful ruler, in exile in the Forest of Arden, and the inseparable friend of the usurping Duke Frederick's daughter, Celia. Perhaps the production's stepped-up focus on music makes the show more marketable, to borrow Celia's observation on the benefit of being news-crammed.

Ramon Hutchins' full-throated performances of the show's songs, accompanied compatibly by a rootsy onstage band, open and close the show. As Lord Amiens, Hutchins initially pumps up the crowd and launches the intermittent songfest, only to be cruelly checked by black-shirted ruffians in service to the usurping Duke Frederick, in Ben Tebbe's performance a vicious control freak obsessed with loyalty (why does that description feel so familiar?).

The opposition between the corrupt court and the Forest of Arden, the arena of escape where most of the action takes place, is thus brilliantly set forth in an imaginative stroke of theater. Overlaying song so thoroughly on the last scene, however, deprives the play's conclusion of an old-fashioned ceremoniousness. Shakespeare's carefully engineered happy ending becomes mainly an occasion to party. Probably Ryan Artzberger, a well-regarded actor and IndyShakes member making his debut as a director, found the symbolic figure of Hymen, who helps tie up various knots at the end, too dated.

That feeling also may have prompted the cutting of the Epilogue, which gives Rosalind her last display of humanity and gentle learning, imparting lessons in love that she has mastered over the course of the play. Understanding that almost all Shakespeare, with the possible exception of "Macbeth," undergoes trimming in modern productions, I still found some of the cuts regrettable. For instance, and at the risk of sounding all English-majory, there is a plethora of elaborate, balanced sentences and laboriously extruded conceits that characterize the language of "As You Like It." The style is prevalent in the prose romance from which Shakespeare drew his story, Thomas Lodge's "Rosalynde," which in turn reflected the gaudy "Euphues" by John Lyly, whose excess of highly ornamented prose enjoyed a vogue among word-drunk Elizabethans.

Rosalind, the heroine, the clown Touchstone, and the studious melancholic Jaques all indulge in euphuistic fancies, some of

|

| Rosalind (as the youth Ganymede) keeps an eye on her pupil, Orlando. |

Speaking of Orlando, there's no reason to put off further discussion of this production's success in giving so much vitality to the love-crammed story at its center. Grant Niezgodski gave a well-balanced interpretation of the hero, destined from an early meeting with Rosalind (placed around that wrestling bout) to be the love of her life. He projected the energy and good-heartedness the role requires. Though in his Arden exile Orlando is quite manipulated by Rosalind's romantic designs (surely he must sense she's not the young swain she pretends to be), Niezgodski never seemed like her unwitting plaything.

|

| Country matters; Touchstone (Jaddy Ciucci) woos Audrey (Joanna Bennett) |

But "As You Like It" is Rosalind's play; she dominates its small but still diffuse scale the way John Falstaff dominates the kingdom-defining "Henry IV" plays. Among Shakespeare's women, only Cleopatra has comparably colossal stature. Who can help being won over by her? She's likable from the beginning, and remains so, despite an episode of meanness when she tries to redirect Phebe's affections.

This production has a strong, winning portrayal of Rosalind by Lauren Briggeman. Her vocal command ranges from tremulous enthrallment as she falls instantly in love with Orlando, through vigorous upbraiding of Duke Frederick as he exiles her, to the credible low timbre she projects in her Arden disguise as a man. Rosalind is learning about love even as she exercises mastery over its intricacies, and Briggeman charmingly sustained that difficult balance.

That's why I would like to have heard her whole speech that ends with the marvelous rhetorical flourish: "Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love." The two examples Rosalind gives before this conclusion illustrate her good education as well as providing support for her argument. Despite their absence here, the line stunningly turns the certainty of death into something that happens "from time to time," and the decay associated with it into a peculiar phenomenon separate from and inferior to love. Rosalind lives by this paradox, by love's supremacy and its right to triumph over all odds. Seeing Rosalind in bridal dress in the last scene brings me close to tears every time, whether attending a performance or reading the play. She has learned so much, and she has taught everybody.

Two other performances stand out for me in this production: Bill Simmons, in broad-brimmed hat and loose summertime clothing as the banished Duke Senior, glides about the stage, spreading his arms as he extols the virtues of life in the forest. His sententious praise is lofted in life-affirming, motivational-speaker tones. The portrayal was just fatuous enough to be delightful without caricature. He reminded me of a typical interview guest on Krista Tippett's "On Being."

I must also mention Josh Coomer's spot-on rendering of Jaques, a lord attending Duke Senior who takes his cue from exile to become a figure of well-rehearsed melancholy, finding every human condition lamentable. Jaques' melancholy is a pose, embedded in a man feeling rootless in rusticity and casting about for a way to distinguish himself in inhospitable surroundings. To represent someone stuffed with attitudes without overacting is no small achievement, and Coomer handled it with aplomb. The touch of satire in his noble set-piece, the "seven ages of man" speech, helped it be the kind of highlight it's supposed to be.

[Photos by Julie Curry]

Comments

Post a Comment